NZ’s evidence-based response to COVID has saved lives – we could do better when it comes to other major diseases

16 March 2023

Jim Mann, University of Otago; originally published in The Conversation.

As we emerge from the COVID pandemic, we’re grateful research evidence was there to guide us.

Years of immunology and molecular research facilitated the rapid development of new vaccines. Modelling expertise helped predict and plan our pandemic response. Research on medications and antiviral drugs enabled them to be adapted to combat the new virus.

The government’s pandemic response resulted in far fewer deaths in this country than in other parts of the world. This is in part because the latest research evidence informed the response.

There are few similar structures to advise government about the ongoing burden of non-communicable diseases, including heart disease, obesity and diabetes. This leaves Aotearoa New Zealand with large gaps in the pathways for translating research evidence into health policy and practice for our major causes of death and disability.

World Health Organization data from 2019 show non-communicable diseases caused 90% of all deaths in New Zealand. Better use of research evidence could save lives and healthcare dollars, as shown by a 2021 report on the cost of type 2 diabetes.

Four evidence-based interventions to prevent or treat type 2 diabetes were modelled and, if implemented, were predicted to save hundreds of millions of dollars. But only one has been implemented so far.

Lack of expertise and transparency

The current disconnect between research evidence and its uptake into policy and practice hasn’t always existed. Several entities once played important roles in translating evidence into policy, including the New Zealand Guidelines Group, the Public Health Commission, the National Health Committee and the Social Policy Evaluation and Research Unit. They have all been disbanded.

In some cases they have been replaced by ad hoc advisory processes, which often lack transparency.

Of course, not all research can, or should, be implemented. But New Zealand researchers have become increasingly frustrated with the difficulty of bringing their own and relevant international research to the attention of policymakers.

Recognising this problem, the Healthier Lives National Science Challenge produced a report that reflects the experiences of leading researchers and community health providers who attended an earlier workshop.

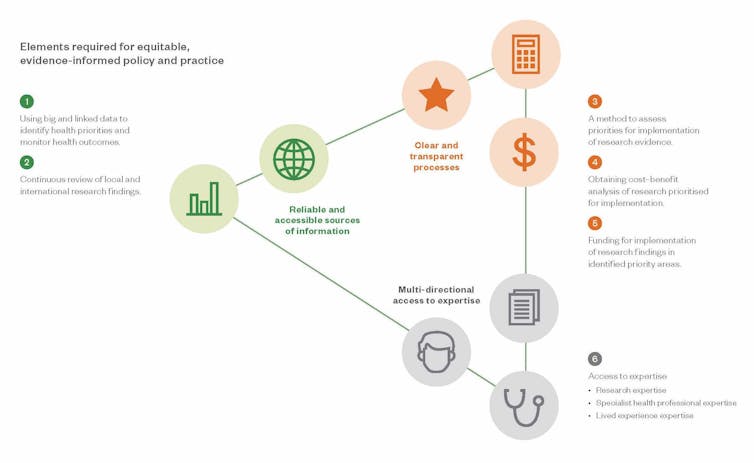

The report identifies elements required for bringing research innovation into our healthcare system.

These include:

- the use of data to identify the most pressing health priorities

- continuous reviews of local and international research findings

- cost–benefit analyses to assess which research evidence should be prioritised for implementation

- funding streams for implementing evidence-informed improvements to healthcare.

It is centrally important that policymakers have access to expertise. This must include not only the expertise of researchers but also of health professionals and people with lived experience of using the healthcare system.

Evidence is available

Several research groups in Aotearoa are trying hard to make evidence as accessible as possible to policymakers. The recently launched Public Health Communication Centre, led by Professor Michael Baker at the University of Otago Wellington, aims to improve communication of public health research findings to support good policy responses.

A former director-general of health, Ashley Bloomfield, was recently appointed to lead the University of Auckland’s new Public Policy Impact Institute. Its aim is to support the application of research into policies that directly impact communities.

Healthier Lives has established an implementation network to bring researchers and community-based health providers together to help take innovative health programmes from research into community practice.

Despite these and other initiatives, it is still unclear what mechanisms there are within government to receive and assess all this evidence and to prioritise it for implementation.

Using evidence to improve New Zealanders’ health

How do other countries use evidence to inform health decision-making processes?

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) produces evidence-based recommendations developed by independent committees with both professional and lay membership. In Finland, a country of similar size to New Zealand, the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare carries out extensive research on population health and provides evidence-based information to support government decision-making.

A significant amount of New Zealand taxpayers’ money is spent on health research ($140 million per year). According to the 2020 Kantar NZHR opinion poll, New Zealanders consider this investment a high priority. They want to see it leading to improvements in the healthcare system and preventive programmes.

New Zealand researchers produce high-quality evidence that could improve people’s health here and around the world. Conversely, a lot of international research is relevant here. We should be taking full advantage of this.

As Aotearoa New Zealand continues reforming its health system, we’re hopeful that transparent and adequately resourced mechanisms will be put in place within government to assess and prioritise research evidence. The recently established Public Health Advisory Committee is a step in the right direction.

To make sure research informs health policy is not a trivial undertaking. But it is necessary if we are to maximise our investment in health research and ultimately improve the health and wellbeing of all New Zealanders.

Jim Mann, Professor of Medicine and Director, Healthier Lives–He Oranga Hauora National Science Challenge and Co-Director, Edgar Diabetes and Obesity Research Centre, University of Otago

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.